Inside: Why does labelling emotions help children regulate their emotions? How can we label emotions? What are the words to use? What books can we use to teach children to label emotions?

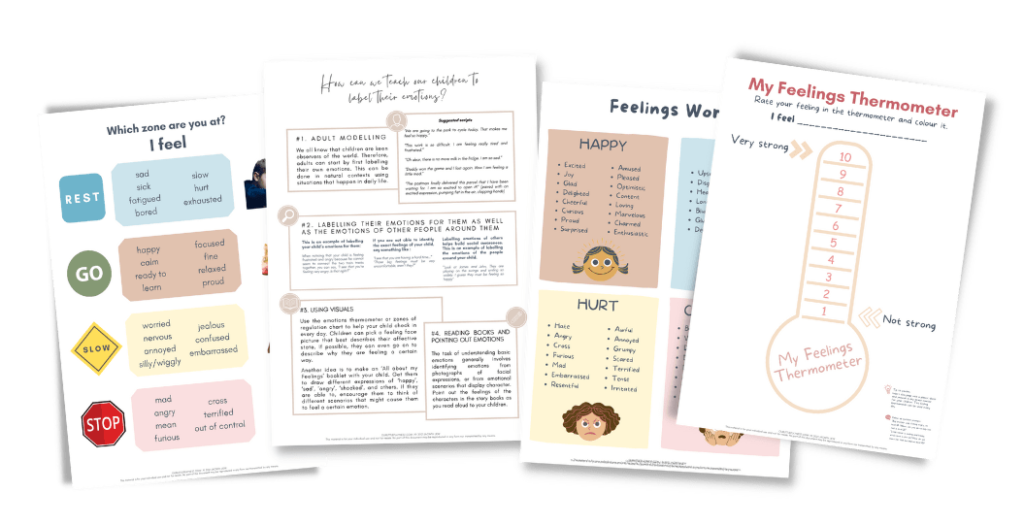

Free download: Includes refrigerator summary sheet on labelling emotions, Feelings Thermometer, Feelings Vocabulary Words Lists, Zones of Regulation Chart and and Feelings drawing activity template.

Imagine this scenario (it might be familiar to many of us!): your child is putting all of his focus on making a very tall tower using magnetic tiles. As the tower gets taller, it starts getting wobbly and your child is visibly anxious. He stands on his tippy toes and stretches as high as he can to put the next piece. He accidentally knocks it over with his elbow and the entire tower comes tumbling down. Before you know it, all the tiles are sitting in a heap on the floor. Your child stares in disbelief. He throws himself on the floor and starts crying, screaming and kicking.

Instead of pulling him up and getting him to try again immediately, you simply hold space and say, “You must be so frustrated”. He looks up at you through his tears and immediately feels better. Through this simple act of validating your child’s feelings, he or she feels seen, heard and most importantly, understood.

Children are often told to “stop it,” “it’s okay, you’re a big boy. You don’t have to cry” or “calm down now. Everyone’s looking”. To their young minds, the message that we are sending when we tell them these things is this: “Stop showing your emotions. Negative emotions are bad”. Children need to understand that having different emotions and feelings are perfectly normal, even through adulthood. This is why labelling your child’s emotions is so vital for their emotional development.

Why is the ability to label emotions so important?

1. It affects your child’s social and cognitive development

Being able to label emotions (their own and the people around them) is a foundational and crucial step to a child’s emotional development. Research (Denham, S. A., & Burton, R. 1996) has shown that children who have a strong foundation in emotional development are better able to deal with their frustrations, get into fewer fights with their peers, and engage in less self-destructive behavior than children who do not have a strong foundation.

Consider these two examples:

Example 1:

Jacob (5yo) has decided to play with a train set during Free Play time. He begins to link wooden tracks together to form a path for his trains to travel on. He realises that the wooden bridge is missing. He digs into the toy box frantically but could not find what he was looking for. As he continues his search in the other toy boxes, he starts to get increasingly upset. In his frustration, he kicks a toy box next to him. “Teacher! Teacher! I want bridge!” He shouts and stomps his feet as he cries out in the direction of a teacher who is busy attending to another child. Suddenly, Jacob spotted the wooden bridge perched on the edge of a chair. His classmate, Sophia, was pretending that it was a slide for her dolls. Jacob rushes over to Sophia, shouting, “THAT’S MINE!” He kicks the chair away and snatches the bridge away from her. When the class teacher finally got to Jacob and took the bridge away from him, he had already launched into a full meltdown and was inconsolable even though she kept telling him to ‘stop crying and calm down first’.

Example 2:

It is Art and Craft time for four-year old Oliver. His teacher is giving out coloured paper to everyone so they can start their craft work. She holds a stack of brightly-coloured paper while walking down the aisle. Oliver spots the purple-coloured paper and knows immediately that that would be his choice. As he is seated in the second last row, he waits patiently for his turn. Two classmates have already chosen purple. By now, Oliver starts to get a little anxious. He controls himself from shouting out loud, “Ms. Nina! I want the purple one!” It’s almost his turn now. His classmate who is seated in front of him just chose purple. Ms. Nina is standing right in front of Oliver now with a stack of paper but there is no more purple. Oliver lowers his head in disappointment and mutters, “I really wanted the purple paper. I’m very sad”. Ms Nina responds, “Oh dear, that must be a terrible feeling. I would be very sad too. Let’s think of how we can solve our problem, shall we?” Oliver instantly feels validated and slightly better. He quips, “It’s okay! I’ll choose yellow today and I’ll choose purple another day!”

In the examples described above, we can see a stark difference in Oliver and Jacob’s ability to label their emotions. Jacob has difficulty labelling his feeling of anger and thus he was not able to seek help or approach his classmate in an appropriate manner. Being able to identify and label his emotions, Oliver is able to express himself to his teacher and to seek for help appropriately. He is also less impulsive and better able to problem solve when an undesirable situation occurs.

2. It affects your child’s language development

The relationship between language and emotional development is bi-directional. For example, a child who is dysregulated and overwhelmed will have difficulty engaging and interacting which, in turn, limits opportunities for language learning to occur. Children need to be calm and present for them to learn optimally and to participate actively. However, if a child is having difficulty regulating his emotions, his amygdala would be triggered to go into a fight, flight or freeze mode. The learning centers in the prefrontal cortex shut down and thus, he would not be at an optimal level to learn.

3. It reduces problem behaviours and helps with self-regulation

When a child is better able to label his emotions, he can also ask for help from the adults around him. Often, children display problem behaviours such as biting, hitting, lying on the floor and screaming, because they are feeling a certain emotion and they do not know how to communicate that. Therefore, they communicate their emotions by displaying these undesirable behaviours.

Researchers (Denham, 1986) have seen fewer challenging behaviors and more developmentally appropriate peer social interactions in classrooms that allocate planned attention to helping children acquire a wider range of vocabulary for emotions.

Does labelling emotions really work?

Research shows that when our children label their emotions, the amygdala becomes less active, while the executive part of the brain, the right ventrolateral prefrontal cortex becomes more active. When emotions are being processed, children are less likely to go into the fight and flight mode.

“But my children cry even more when I label his emotions!”

Many think that labelling “doesn’t work” because children cry even more. Crying is healing. After children feel seen and heard, they release their big feelings inside them, and crying is one way to cope. It doesn’t mean that labelling is not working. In fact, it is helpful because children feel better after releasing their emotional backpack! In the process, they learn emotion regulation!

How can we teach our children to label their emotions?

#1 Adult modelling

We all know that children are keen observers of the world. Therefore, adults can start by first labelling their own emotions. This can be done in natural contexts using situations that happen in daily life.

Suggested Scripts:

“We are going to the park to cycle today. That makes me feel so happy.”

“This work is so difficult. I am feeling really tired and frustrated.”

“Oh dear, there is no more milk in the fridge. I am so sad.”

“Daddy won the game and I lost again. Now I am feeling a little mad.”

“The postman finally delivered this parcel that I have been waiting for. I am so excited to open it!” (paired with an excited expression, pumping fist in the air, clapping hands)

#2 Labelling their emotions for them as well as the emotions of other people around them

This is an example of labelling your child’s emotions for them: When noticing that your child is feeling frustrated and angry because he cannot seem to connect the two train tracks together, you can say, “I see that you’re feeling very frustrated. You can’t seem to get the tracks together!”

If you are not able to identify the exact feelings of your child, say something like, “I see that you are having a hard time…” “Those big feelings must be very uncomfortable, aren’t they?”

Labelling emotions of others helps build social awareness. This is an example of labelling the emotions of the people around your child. “Look at James and John. They are playing on the swings and smiling so widely. I guess they must be feeling so happy”

#3 Using visuals

Use the emotions thermometer or zones of regulation chart to help your child check in every day. Children can pick a feeling face picture that best describes their affective state. If possible, they can even go on to describe why they are feeling a certain way.

You can find the Feelings Thermometer, Feelings Vocabulary Words List, Zones of Regulation Chart and and Feelings drawing activity template inside the Resource Guide to Labelling Emotions. Click the link at the end of the post to download the free resource guide.

Another idea is to make an ‘All about my Feelings’ booklet with your child. Get them to draw different expressions of ‘happy’, ‘sad’, ‘angry’, ‘shocked’, and others. If they are able to, encourage them to think of different scenarios that might cause them to feel a certain emotion.

#4 Reading books and pointing out emotions

The task of developing understanding basic emotions generally involves identifying emotions from photographs of facial expressions, or from emotional scenarios that display character. Do point out the feelings of the characters in the story books as you read aloud to your children.

Here are some books that are great for teaching the labelling of emotions:

Toddlers to preschoolers

- Glad Monster, Sad Monster: A Book About Feelings by Anne Miranda & Ed Emberley

- My Many Colored Days by Dr. Seuss

- Today I Feel…. An Alphabet of Feelings by Madalena Moniz

- When Sophie Gets Angry- Really, Really Angry…by Molly Garrett Bang

- My Book of Feelings: Exploring a world of emotion by Nicola Edwards

Preschoolers

- On Monday when it rained by Cherryl Kachenmeister

- The way I feel by Janan Cain

Preschoolers to lower primary

- Feelings (Reading Rainbow Book) by Aliki

- “All About Feelings” Usborne

- When I Feel Angry by Cornelia Maude Spelman

- I’m Mad (Dealing With Feelings) by Elizabeth Crary

- I’m Frustrated (Dealing With Feelings) by Elizabeth Crary

Free Download: Resource Guide to Labelling Emotions

Includes refrigerator summary sheet on labelling emotions, Feelings Thermometer, Feelings Vocabulary Words Lists, Zones of Regulation Chart and and Feelings drawing activity template.

References:

Denham, S. A., & Burton, R. (1996). A social-emotional intervention for at-risk 4-year-olds. Journal of School Psychology, 34(3),225-245.

Joseph, G. E., & Strain, P. S. (2003). Enhancing emotional vocabulary in young children. Young Exceptional Children, 6(4), 18-26.

Joseph, G. E., & Strain, P. S. (2003). Helping young children control anger and handle disappointment. Young Exceptional Children,7(1), 21-29.

Shure, M. B. (2000). I can problem solve: An interpersonal cognitive problem-solving program. Champaign, IL: Research Press.

Webster-Stratton, C. (1999). How to promote children’s social and emotional competence. London: Paul Chapman

Denham, S. A. (1986). Social cognition, prosocial behavior and emotion in preschoolers: Contextual validation. Child Development, 57, 194-201.